Course Design: A Systematic Approach

Following the steps of a widely accepted Instructional Design (ID) model can assist instructors in preparing and delivering meaningful and effective instruction. As Smith and Ragan (1999) explain, “The term instructional design refers to the systematic and reflective process of translating the principles of learning and instruction into plans for instructional materials, activities, information resources, and evaluation.” It is during this process that you should consider the audience for whom the instruction is designed, what goals drive the instruction, and which objectives students will follow to ensure they do what you want them to do.

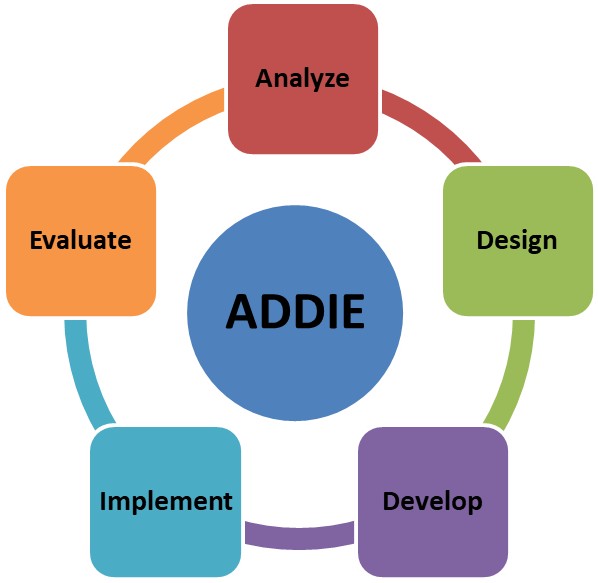

Essentially, Instructional Design (ID) is a process that can help improve the design and development of courses and course content. Often associated with training in business and industry, ID has been widely used by educators to revise and modify existing courses and to plan and implement new instruction. The process is systematic and systemic; steps are taken in the design (planning) phase of the course that are dependent upon each other to generate a successful product (course). One of the more tried and true ID models is ADDIE (Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, Evaluate). The ADDIE model is presented in the following graphic.

Instructional Design (ID) is a process that can help improve the design and development of courses and course content.

Analyze

When using the ADDIE model, the first step is to analyze and understand all aspects of the instructional problem. In other words, what are our learning objectives, what are the physical or organizational limitations of the course, what are the technical requirements or limitations, why are we teaching what we teach, who are our learners (students), and how will instruction get our students to where we want them to be at the end of the semester? Knowing your students, for instance, will help guide your course design, so it could be a good place to begin. Even if the semester is about to begin or already has begun, it’s a good idea to know your students, their characteristics, and their needs.

Knowing your students will help guide your course design and even if the semester is about to begin or already has begun, it’s good to know something about your students.

Example

Have students take a self-assessment inventory at the beginning of the semester to better acquaint you with the skills and knowledge they bring to the course. The inventory could include questions related to the course content, i.e. “What events lead to the American Civil War?” or “How many groups are represented in the Periodic Table of Elements?” or they could be more general, i.e. “What skills do you bring to this class?”

Design

In the design phase, consider all components of instruction from beginning to the end. When designing instruction, it often helps to work backward and think about how you will evaluate, implement, and develop materials, methods, and media that facilitate instruction. This is the creative and inventive phase in which you can collaborate with colleagues and be open to new techniques and approaches. During the design phase, write learning objectives for events and tasks required of students, determine which methods (lecture, demonstration, group work), materials (handouts, lab equipment, artifacts, flip charts) and media (computer multimedia, video, audio) will be incorporated into the course. Keep in mind that all materials, methods, and media should be carefully selected based on the learning objectives. Effective instruction should be well-planned, and nothing should be designed arbitrarily.

Keep in mind that all materials, methods, and media should be carefully selected based on the learning objectives.

Example

Identify what students are supposed to learn in the course and write instructional objectives for each of them (see the Instructional Guide section on Learning Theory for help with this); decide what kinds of handouts and/or worksheets will be used for particular content areas; determine how many examinations and/or quizzes will be given during the semester; and identify which active learning techniques and activities could be used to achieve module- and course-level objectives.

Development

Development (or production) is the step where you actually create the “things” used in teaching: the lecture material, the website that supports the course, the handouts and assessment rubrics that instructors and students will use, the PowerPoint presentations, and the case study videos. You will have to decide whether to create instructional products yourself or to employ an expert to create them. Ask yourself whether you can get by with an existing product and if it can be modified or if you should begin from scratch. Time is of the essence at this point, and efficient instructional design relies on best practice, from planning to evaluation.

You will have to decide whether to create instructional products yourself or to employ an expert to create them.

Validate what you develop during this phase—this is sometimes called rapid prototyping (or continuous evaluation). Validation, or prototyping, helps ensure that the delivery of your designed material goes well and is aligned with goals and learning objectives. In essence, prototyping keeps things running smoothly and minimizes potential problems later in the semester.

Example

Create an active learning activity conceptualized in the design phase—i.e. prepare the actual materials that will be used for the activity.

Implement

Implement is where the actual instruction takes place. Students rely on the expertise of their instructors to present content in a meaningful way. At the same time, students should be engaged in the learning process. All of the planning done in the design and development stages is on stage in the implementation phase. This is where the instructor’s expertise shines along with the crafted approach to teaching, whether the setting is a classroom, a lab, a field setting, or online. Implementation, then, involves facilitation of learning.

Students rely on the expertise of their instructors to present content in a meaningful way.

Example

After going through the design and develop phases in preparing course materials, now is the time to follow the plan and teach the course. It’s a good idea to keep an ongoing record of the effective and the not-so-effective aspects of the implementation phase (this will be covered in more detail in the next phase). These notations (known as formative evaluation) will help you improve your delivery of subsequent material, either during the next class period or in the next semester.

Evaluate

Evaluation happens at two levels: formative, which tells us what is occurring, and summative, which tells us what has occurred. Formative evaluation takes place during the planning and instruction phases and assesses what instructors and students are doing. Summative evaluation occurs after instruction—here we can evaluate the instruction and what the students have done. Evaluation tells us whether the students have participated in learning and met the instructional objectives. With data in hand, instructors need to ask, “How can I modify my instruction to improve its next presentation?”

Evaluation happens at two levels: formative, which tells us what is occurring, and summative which tells us what has occurred.

Examples

Formative

- Keep a notebook of what happened during the class period – how well an activity went, the feedback received from the students, your thoughts and feelings about the lecture or activity. Use these notes to plan new activities, lectures, and assessments.

- Elicit feedback from students at the end of a class period, every two-to-three weeks, or midway through the semester. This form of feedback could be as simple as a few questions on their impression of a particular lecture or activity, questions they might have on content, or how they feel about their own progress in the class. This information provides a snapshot of the course and indicates whether any adjustments need to be made.

Summative

Engage students in a project or culminating activity in which they must apply what they have learned. If the results are less than what you had expected, determine the cause (could the delivery method be inappropriate for the content or are students not reading the material?) and proceed from there (have students been given adequate time to practice the material or does the material need to be presented in a different way?).

Summary

An instructional design process like ADDIE can be used to create effective instruction which will be meaningful for instructors and students alike. Following the basic processes and procedures that constitute instructional design, faculty can become more efficient in development of their courses and approaches to facilitating their students’ learning.

References

Smith, P. L., & Ragan, T. J. (1999). Instructional design (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Selected Resources

Mager, R. F. (1997). Making instruction work: A step-by-step guide to designing and developing instruction that works (2nd ed). Atlanta, GA: CEP Press.

Mager, R. F. (1997). Preparing instructional objectives: A critical tool in the development of effective instruction (3rd ed). Atlanta, GA: CEP Press.

Molenda, M. (2003). In search of the elusive ADDIE model. Performance Improvement. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Michael_Molenda/publication/251405713_In_search_of_the_elusive_ADDIE_model/links/5b5f098ba6fdccf0b200e5b2/In-search-of-the-elusive-ADDIE-model.pdf

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Suggested citation

Northern Illinois University Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. (2020). Course design: A systematic approach. In Instructional guide for university faculty and teaching assistants. Retrieved from https://www.niu.edu/citl/resources/guides/instructional-guidee