Changing Habits

We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.

–Aristotle

Introduction

Have you ever stopped to think about your habits or how they impact your daily life? Have you ever needed to change your habits because of a new environment like online learning or campus life? According to experts with Psychology Today, habits form when new behaviors become automatic and are enacted with minimum conscious awareness. That’s because “the behavioral patterns we repeat most often are literally etched into our neural pathways.”

Think about that last quote for a moment. Now, think about habits you do automatically. For example, how many times a day do you pick up your mobile phone to read text messages, wander on Facebook, or check your Instagram account? Did you actively think to yourself, “It’s time to check Instagram now?” Or did it just happen without much conscious effort?

While some habits can be detrimental, such as wasting an hour on Twitter when you should be studying, others can be great to have around. Learning to brush your teeth when you were young helps you have good dental health when you’re older. Another example is shutting off the lights when you leave a room. That habit helps save on your energy bill.

Understanding Habit Formation

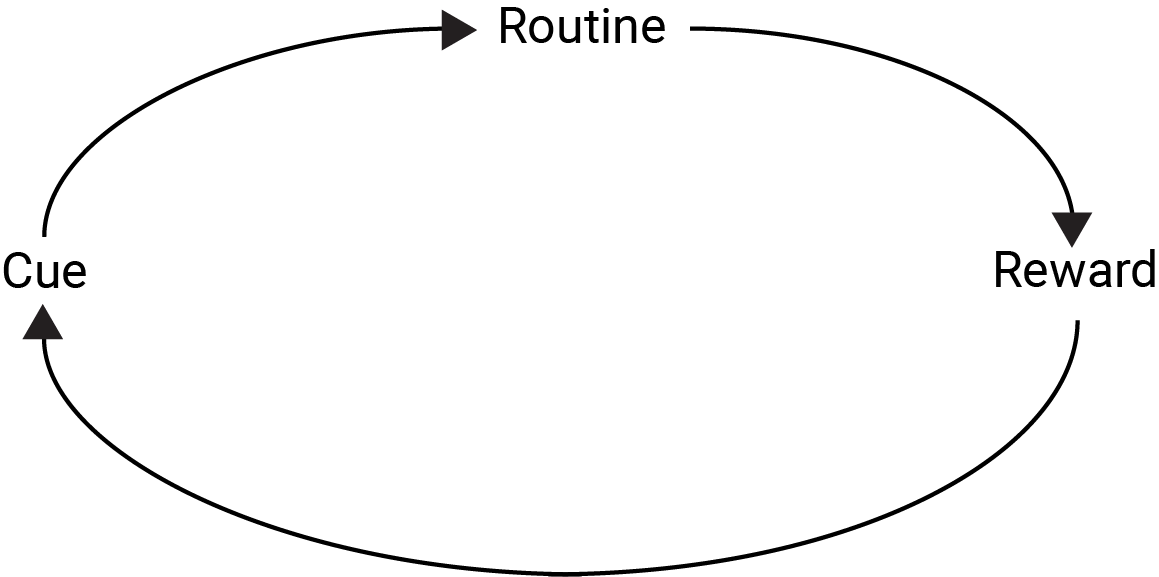

In the Power of Habit, Duhigg (2012) explains that MIT researchers discovered a three-step neurological pattern that forms the core of every habit (see figure 1). The first step is cue. It is a trigger that tells your brain to go into automatic mode and prompts the behavior to unfold. The second step is routine, which is the behavior itself and the action you take. The last step is reward. It helps your brain determine if a particular habit loop is worth remembering or not. Generally, habits have immediate or latent rewards. Habits with immediate rewards are easier to pick up and condition, whereas those with delayed rewards are more difficult to commit to and maintain. Think about how easy it is to check your iPhone compared to exercising more.

Cue: Your cell phone receives a push notification that someone likes or commented on one of your photos. The notification serves as a cue (or trigger) that tells you to check your account.

Routine: This is the actual behavior. When you receive the push notification, you automatically check your Instagram account.

Reward: This is the benefit you gain from doing the behavior (e.g., finding out who likes or commented on one of your photos). Recall that the reward helps the brain figure out if this particular loop is worth remembering for the future.

Because some habits are beneficial, let’s take a closer look at the example of turning out the lights when you leave a room.

Cue: The light tells your brain to go into automatic mode and which habit to use when leaving the room.

Routine: The actual behavior of turning out the light.

Reward: A lower utility bill and better overall home energy budget.

Changing the Habit Loop

Now that you have an understanding of how habits form, let’s turn attention to changing them. Consider the following scenario:

One way would be to convince your friends to meet in the library and spend a couple of hours studying together. Afterward, you could treat yourselves at Starbucks. Another routine would be to study on your own and then meet your friends at Starbucks.

In either case, you replace a negative routine (going to Starbucks before studying) with a healthier one (studying before going to Starbucks). By changing these routines, you keep the reward of socializing with your friends while gaining new ones: earning better grades. By changing your routine, you increase your chances of earning multiple rewards.

Let’s plug this new routine into the habit loop to see how it works.

Cue: The time your class ends tells your brain which habit to employ. If you want to be extra ambitious, you could create a calendar notification on your computer or mobile device.

Routine: Studying after class with friends or alone.

Reward: Socializing with friends at Starbucks after studying; earning better grades.

Putting What We Know into Practice

The next step is to think about a habit you want to change. That begins by first describing the habit. Below are a few questions to help get you started. They were developed by Claiborn and Pedrick (2001), authors of The Habit Change Workbook.

- Identify a habit you would like to change.

- When did the habit begin, or when do you first remember doing it?

- Has the habit changed over time? If so, describe the changes that you have noticed.

- When do you typically engage in the habitual behavior (day and time)?

- Do you engage in the habit in a specific location?

- What else is usually happening in your life when the habit occurs?

- Does your behavior affect other people or facets of your life?

- What does the habit do for you?

- How happy (or unhappy) are you as result of your habits, or what are the rewards.

Second, you need to understand how the habit operates by diagnosing its cue, routine and reward. This will help you to gain power over it and begin making changes you seek to make.

- What is the Habit? _________________________

- What is the Cue? __________________________

- What is the Routine? _______________________

- What is the Reward? _______________________

Because a habit is a formula that the mind automatically follows, you need to re-engineer that formula by creating a new habit loop. In the spaces below, think of a healthy routine by planning for the cue and choosing a behavioral pattern that yields the reward you want. You may provide a list of multiple routines before settling on one. In addition, the reward does not need to be overly elaborate. The goal is to establish a positive association with putting the habit into practice.

- What is the Habit? _________________________

- What is the Cue? __________________________

- What is the Routine? _______________________

- What is the Reward? _______________________

It is important to note that telling yourself there is a reward is not enough for a habit to stick. According to Duhigg, one way to get a habit to stick is to repeat it. In other words, repetition is important if you want your brain to crave the reward. He notes that “countless studies have shown that a cue and a reward, on their own, aren’t enough for a new habit to last. Only when your brain starts expecting the reward—craving the endorphins or sense of accomplishment—will it become automatic” (p. 51).

Anticipating Pitfalls

In a two-year study that examines the rate of self-change attempts of New Year’s resolvers, Norcross and Vangarelli (1988) note that 77% of resolution-makers maintained pledges for one week. However, only 19% of them kept their resolutions after two years. If this statistic is indicative of habits in general, “at least 8 times out of 10, you are more likely to fall back into your old habits and patterns than you are to stick with a new behavior” (Clear, 2015).

So the question is: how do you make new habits stick when the odds are not in your favor? You learned that repetition is an important factor, but that is only one piece of the puzzle. Experts agree that maintaining healthy habits require you to anticipate pitfalls. Listed below are a few common mistakes that people make and some solutions that can help you navigate around these hazards and toward healthy behavior patterns.

Pitfall 1: Trying to change everything at one time.

Solution: Try to pick one thing and do it well.

The following scenario is one you know too well. You start creating a new habit by first generating a list of things you hope to change or adopt. You tell yourself you have the willpower to succeed and you start off doing quite well. Then life responsibilities start piling up or the persistent urge to indulge in old habits kicks in. Before you know it, you feel overwhelmed and slowly revert to old behavior patterns. For example, if you suddenly shift to working from home when you’re used to working in the library or going to a coffee shop, you might slip into old habits like watching TV or going to the kitchen to grab a snack.

So, how do you avoid this “overwhelmed” feeling? In “The Power Less,” Leo Babauta (2009) suggests changing one habit at a time and focusing on doing it well before moving on to the next one. He recommends creating a list of behavioral changes you want to make and then chunking them based on which one you want to accomplish first. The key is focusing on the one goal, and after it becomes a ritual you move on to the next one.

If you find yourself struggling to pick a habit from the list of changes, try asking the following questions:

- Which goal is going to pull the rest of your life in line? This is referred to as focusing on a “keystone habit” (Clear, 2015; Duhigg, 2012).

- Focus on the small steps and take your time.

- What is the ripple effect of the keystone habit? In other words, what are the primary and secondary benefits of changing the habit? For example, exercising regularly leads to more energy (primary) and results in better sleep and focused study habits (secondary).

Pitfall 2: Trying to begin with a large habit.

Solution: Try to make the habit “so easy you can’t say no” (Babauta, 2013, qtd. in Clear, 2015).

You know that starting a new habit is difficult. And when you try to achieve the result you want right away with max effort, you tend to increase that difficulty and set yourself up for failure. Take the goal of developing a habit of exercising regularly. You start off by working out an hour or two everyday. After a week or so you discover that devoting a large amount of time to a new exercise regimen, when the body is not used to a workout routine, is too difficult to maintain. Ultimately, you give up. Most everyone has experienced a situation like that before.

According to habits experts, the goal should be to start small and easy, build up to thirty minutes and then to an hour or two. Babauta explains that “actually doing the habit is much more important than how much you do.” He says:

If you want to exercise, it’s more important that you actually do the exercise on a regular basis, rather than doing enough to get a benefit right away. Sure, maybe you need 30 minutes of exercise to see some fitness improvements, but try doing 30 minutes a day for two weeks. See how far you get, if you haven’t been exercising regularly. Then, if you don’t succeed, try 1-2 minutes a day. See how far you get there.

If you can do two weeks of 1-2 minutes of exercise, you have a strong foundation for a habit. Add another week or two, and the habit is almost ingrained. Once the habit is strong, you can add a few minutes here and there. Soon you’ll be doing 30 minutes on a regular basis—but you started out really small.

Let’s now put this situation in the context of establishing stronger study habits, using the example of studying before hanging out with friends at Starbucks.

Cue: The time your last class ends tells your brain to go into automatic mode and which habit to employ once class is over (i.e., going to the library).

Routine: Studying after class with friends or alone.

Reward: Socializing with friends at Starbucks after studying; earning better grades

It is important to ask how much time is needed for studying. Thirty minutes, one hour, two hours, more? Remember, this is a new routine and you want to avoid failure. If your goal is to study two hours after class, you might start out studying for thirty or forty-five minutes and then lead up to that. Remember, you want to make the habit “so easy you can’t say no” (Babauta, 2013).

Pitfall 3: Not changing your environment.

Solution: Create an environment that promotes accountability and healthy lifestyle.

According to Clear (2015), “if your environment doesn’t change, you probably won’t either.” That means habits are part of your physical and social environment. For example, smelling delicious food is a cue to eat or seeing your television when you get home from work is a cue to sit down and relax for the evening (Jackson, Morrow, Hill & Dishman, 2004). Similarly, receiving a notification on your iPhone everyday at noon or a text message from a friend could be a cue that it is time to study.

You could take this example one step further by filling your environment with motivational posters or post-it notes with inspirational quotes like this: “every journey begins with a single step” (Confucius, philosopher). You could also keep a running record of your results and make it visible. For example, you could report progress in a journal or in social media or a blog. You could even tell your family, friends and colleagues what your goals are and have them send you reminders and encouragement via Twitter, Facebook or text messaging.

Once again, let’s put this situation in the context of establishing stronger study habits. Think about how you might change your physical and social environment. Keep in mind how others might help to hold you accountable. As experts contend, encouragement from friends, family and colleagues provides accountability and support for achieving successful goals (Jackson, Morrow, Hill & Dishman, 2004; Dolan, 2012; Oliveira, 2015). They can keep you on track and provide reminders and, more importantly, the necessary enthusiasm and support for when you feel like you’re going to falter. For example, if you have a hard time staying on task when you work on a larger project, you might decide to have a Zoom meeting with a friend where both of you check in with each other briefly and remain on the call while you work independently. As you work, you can periodically check in with each other to offer support and encouragement.

Creating a Plan

Below are four simple steps for changing one habit at a time (Oliveira, 2015):

- Choose one keystone habit and do it well. It is ideal to select one goal that will bring your life in line. Be sure to start with something easy to achieve and then slowly enhance the degree of difficulty.

- Write down your plan: Try to create a habit loop: cue, routine and reward. Make visible what you will do each day. Remember to start off slow, focusing on creating ritual first and results second. Also, define success in measurable terms.

- Make your goal public and develop a support team: Ask your family, friends or colleagues to help hold you accountable. Be sure to report your progress each day, either within a journal or through your favorite social media outlet.

- Make a plan for when you falter. Write down what caused you to stumble. You want to be as honest as possible. Most importantly, don’t be afraid to start over with a revised plan.

How can technology help?

Need some help changing your habits? Technology can help you with various steps in the habit-formation process:

Calendars as Cues. Using an online calendar like Google Calendar, iCal, or Outlook 365 Calendar can help you schedule the habits you want to build. You can make events that recur monthly, weekly, or daily, and set reminders to let you know it’s time to get started on a task.

Checklists for Chunking Large Projects. Project management websites like Trello and phone apps like Color Note can help you break down large projects into smaller, more manageable tasks. Use these tools to write down small steps, and check each step off as you work. You can even write a step for rewards, so you remember to reinforce good habits!

Habit Trackers. There are also apps designed specifically to help you form good habits, including Streaks, Habitshare, and Habitica. Many of these apps help you assess your habits, break them into small pieces, stay accountable, and reward you for completing your goals.

Works Consulted

Babauta, L. (2013, February 13). The four habits that form habits. Zen Habits: Breathe.

Claiborn, J., & Pedrick, C. (2001). The Habit change workbook: How to break bad habits and form good ones. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Clear, J. (2015). The 3 R’s of habit change: How to start new habits that actually stick [Web log comment].

Dolan, S. (2012, January, 20). Benefits of group exercise. American College of Sports Medicine.

Duhigg, C. (2014). The Power of habit: Why we do what we do in life and business. New York: Random House.

Habit Formation Basics. (2015). Psychology Today. Retrieved from

Jackson, A.W., Morrow, J.R., Hill, D.W., & Dishman, R.K. (2004). Physical activity for health and fitness. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Norcross, J. C., & Vangarelli, D. J. (1988). The resolution solution: Longitudinal examination of New Year’s change attempts. Journal of Substance Abuse, 1, 127–134.

Oliveira, R. (2015, August 25). Change your life – one habit at a time. UC Davis Integrative Medicine Program.

Developed and shared by The Learning Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.