- STEM IE

- Making Content Relevant

- STEM IE Research Findings

STEM IE Research Findings

Youths’ perceptions about what they are learning are likely to be shaped by whether they understand how activities and content are relevant outside the immediate context. The extent to which students perceive particular activities or subjects as meaningful is certainly likely to be influenced by a variety of factors that students bring with them to the program, such as their own interests and stereotypes. Yet we know relatively little about the ways that ALs attempt to communicate relevance to their students during everyday activities or whether these communications have any real impact on the way youth view what they are learning.

How Often ALs Talked About Relevance of Content

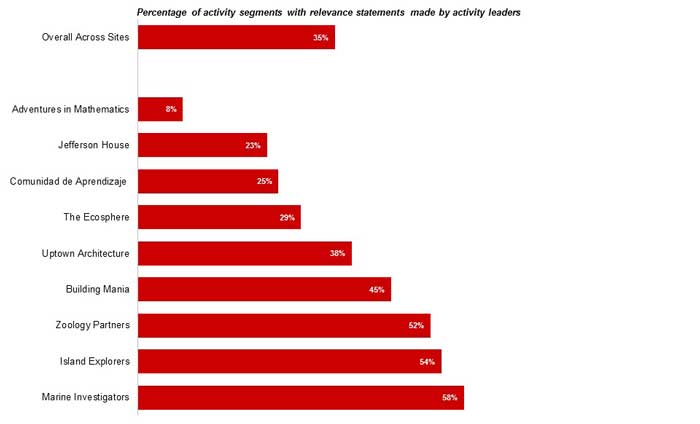

We used several sources of data in our analysis of how making content relevant mattered to youth. We counted every time an AL talked about the relevance of the content that youth were experiencing within approximately 15 minute periods prior to the youth Experience Sampling report. If ALs talked or asked youth about how what they were learning was relevant to things like addressing local problems in their communities, careers, daily routines, and current events, that comment was counted as talking about the relevance of content. As shown in Figures 1 and 2, we found a large degree of variation both across programs and individual activities provided within programs in terms of how frequently relevance statements were made by program ALs.

Figure 1. Programs varied in terms of the degree to which activity leaders made relevance statements.

Programs that involved the study of local ecology or species, often in an outdoor community space, had the highest percentage of videotaped activity segments with at least one or more relevance statement(s) made by activity leaders, occurring in the majority of segments (Marine Investigators, Island Explorers, and Zoology Partners). In these three programs specifically, an average of just over two relevance statements

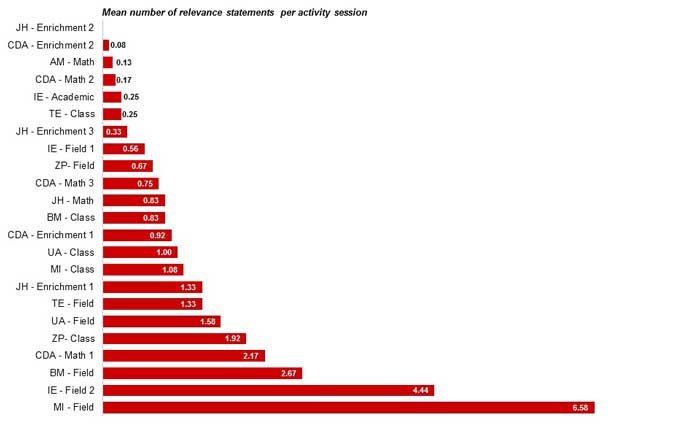

Figure 2. Even

Within most of the programs enrolled in the STEM IE study, activities varied both during the day and across days and were commonly led by different activity leaders. A total of 23 discrete activities were provided across the nine programs enrolled in the study. Although the majority of programs were found to have fewer than one relevance statement made per programming period associated with a given ESM signal, there were two activities in particular, Marine Investigators (MI) - Activity 2 and Island Explorers (IE) - Activity 3, where activity leaders made an average of 6.58 and 4.44 relevance statements per activity session on average. Each of the activities

How Talking About Relevance Mattered to Youth

Youth were signaled four times per day to report how important what they were doing when signaled was: (a) to them, (b) for their future goals, and (c) for use outside the program. They also reported on how engaged they were at the moment and how much they were learning.

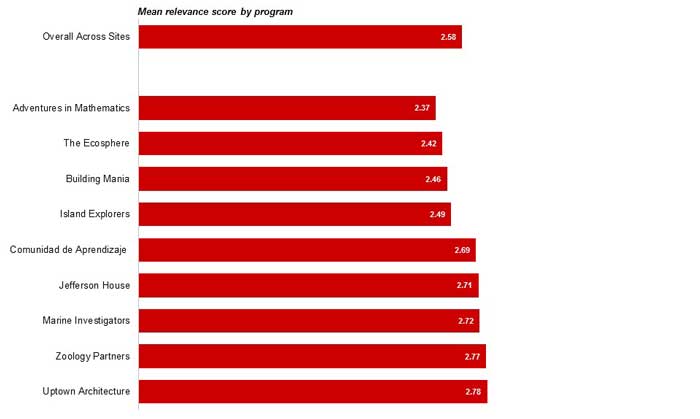

Figure 3. Mean Relevance scores provided by youth in relation to their in-the-moment experiences were less variable across programs.

Scored on a 1 to 4 scale, the program with the highest mean relevance score (Uptown Architecture) was the one project that involved an ongoing group project spanning most of the program that involved designing and constructing an outdoor classroom at the school housing the program. This program offered the greatest opportunities for youth to learn skills and apply them in a real-world setting, have opportunities to experience a sense of agency, and engage in a project that would make a lasting contribution to the school community. Each of these characteristics likely promoted feelings of relevance among participating youth.

Not surprisingly, when ALs talked about the relevance of the activities that youth were doing and the content that they were learning, youth perceived that the activities they were doing were more relevant than if ALs did not talk about content relevance. When youth were engaged in creating a product and their AL talked about the relevance of what they were doing, they found the task to be less difficult, but this was not the case when they were doing other activities.

Contrary to research conducted in school classrooms, ALs’ talk about relevance was not meaningfully related to youth engagement. This finding suggests that informal environments, like STEM summer camps, are different from school classrooms.

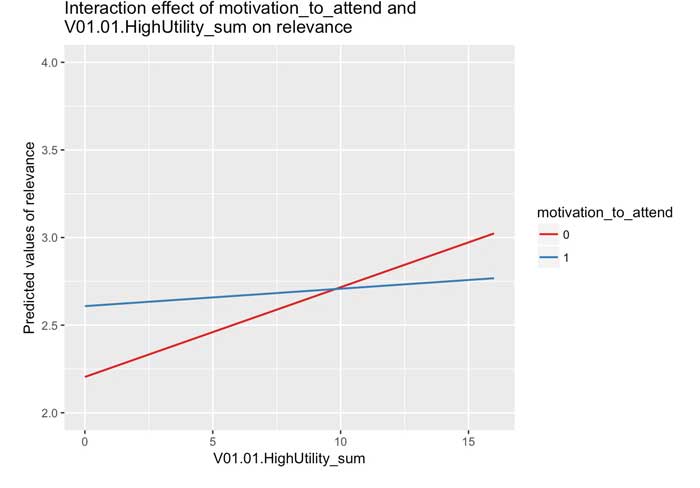

Talk About Relevance Mattered to Some Youth More Than Others

Settings Matter in How Talk About Relevance Impacts Youth

One important characteristic of many of the programs enrolled in the STEM IE study was that there was an intentional effort to link STEM concepts learned about in the classroom to activities undertaken in field-based and community settings. In

We found that when young adolescents were in engaged in educational activities in a meaningful community setting, they reported learning more when ALs made fewer, rather than more, relevance statements. This result was somewhat surprising but potentially important. In this sense, it may be important for learning to allow youth to experience such authentic, field-based contexts

Relevance and the Local Community

Some of the study programs also sought to get youth to think about how STEM could be useful for solving local problems or making a positive contribution to their community. In some cases, programs asked youth to think about the causes of a local, community, and/or environmental problem and potentially undertake projects that were meant to educate others about the problem, present possible solutions, or actually help address the issue. The goal here was to help youth see the relevance of STEM to helping others or addressing community or societal problems. When these types of opportunities were made available to participating youth, youth were more apt to report that what they were doing at the moment was important to them. In this sense, providing youth with opportunities to pursue self-transcendent goals (i.e., activities or projects designed to help youth think about how STEM can be used to make a contribution for the benefit of others) was associated with greater perceptions of relevance. This result may help explain another related finding. Youth enrolled in programs that intentionally provided youth with opportunities to pursue self-transcendent goals were also more apt to report working hard when signaled.